Witnesses against state prisoners in the last Jacobite rising

This week Darren Scott Layne discusses how the British government used witnesses against state prisoners during the last Jacobite rising in 1746.

Nearly a month before the opening salvo of cannon-fire on Culloden Moor, officials within the Hanoverian government of George II were deeply engaged in the task of prosecuting those suspected or known to have been involved with Jacobite rebels. The greatest tool at the government’s disposal toward this end was the collection of testimonies by individuals who had seen such occurrences firsthand, or who had actually been in arms, themselves. Accordingly, policies were drafted and carried out regarding the processing and treatment of these witnesses, whether they were combatants turning King’s evidence to secure some measure of leniency, loyal citizens of the established government wanting to do their part, or ambivalent passers-by who had to be compelled under oath to give their word.

By February 1746, masses of prisoners were already packed beyond capacity within the jails of England and Scotland, and the government was pressed to obtain a sufficient number and quality of witnesses to successfully process the most guilty amongst them.[i] Through the spring and summer of that year, a spirited correspondence was exchanged between the Lord Justice Clerk Andrew Fletcher and King George’s secretary, the Duke of Newcastle, regarding the most efficient (and legal) methods of securing enough evidence to meet these needs.[ii] Their solution lay within the anticipated testimonies of hundreds of witnesses.

Before officially being charged, most prisoners were first briefly examined by the regional sheriffs and deputies of the towns in which they were being held. These pre-trial investigations, or precognitions, were recorded in preparation for a more formal judicial review if deemed necessary. George Miller, sheriff-deputy at Perth, conducted at least 153 individual precognitions between 19 and 28 July 1746 in addition to compiling full examinations of 73 witnesses and prisoners between 10 April and 23 July of the same year.[iii] Fletcher noted to Newcastle that by the middle of March 1746, officers at Perth had compiled over 500 pages of examinations with ‘full proof’ against 250 rebels. Similar arrangements were made in Edinburgh, Aberdeen, Stirling, Lanark, and Dunkeld, though they were often not as formally organised.[iv] As a pair of prisoners was escorted through Kirkcaldy on their way to Edinburgh by thirteen loyal citizens, for example, the officer of excise at Leven described how the local justices simply met them on the road to take statements from each participant.[v]

Fletcher knew that crown judges could lawfully compel witnesses to give evidence, but those not charged with a crime could not be held in custody without a warrant, thereby making the task of securing some informants more difficult. As the Jacobite trials for high treason purposefully took place in England, the many Scottish witnesses who were called up to provide testimony were forced to travel. Some were reluctant to do so due to the costs of the journey and for fear of retribution by still-active rebels.[vi] Newcastle eased the process, however, by giving the Lord Justice Clerk carte blanche to not only pay for their transportation, but to defray all costs for witnesses associated with prosecutions for treason throughout Britain.[vii]

Witnesses were summoned from all parts of the nation to appear at the prominent locations that were to host proper trials for suspected Jacobites: namely Southwark, Carlisle, and York.[viii] John Horn, a farmer in Duddingston, received a letter from a crown solicitor commanding that ‘all other things set aside and ceasing every excuse you be’ to appear in Carlisle on behalf of Charles Spalding of Whitefield. Horn was threatened with a fine of £100 if he would not show.[ix] Robert Morison and Robert Mitchell, bookbinders in Perth, were likewise subpoenaed to speak against Macdonald of Kinlochmoidart under the same threat ‘to testify the truth and give evidence’ on 12 September 1746.[x] At least twenty witnesses were brought to London in October alone to give evidence, including numerous servants of prominent Jacobite elites and eight soldiers who served in rebel regiments.[xi] Particular targets of high value were specifically pursued in the hopes they would provide added intelligence. John MacNaughton, a watchmaker from Edinburgh, was chased through Glenlyon for three miles by government troops. Though only a servant of Jacobite secretary John Murray of Broughton, he was considered to be ‘a Prisoner of Consequence’ by Campbell of Glenorchy and ‘can make considerable discoveries’ if properly examined.[xii]

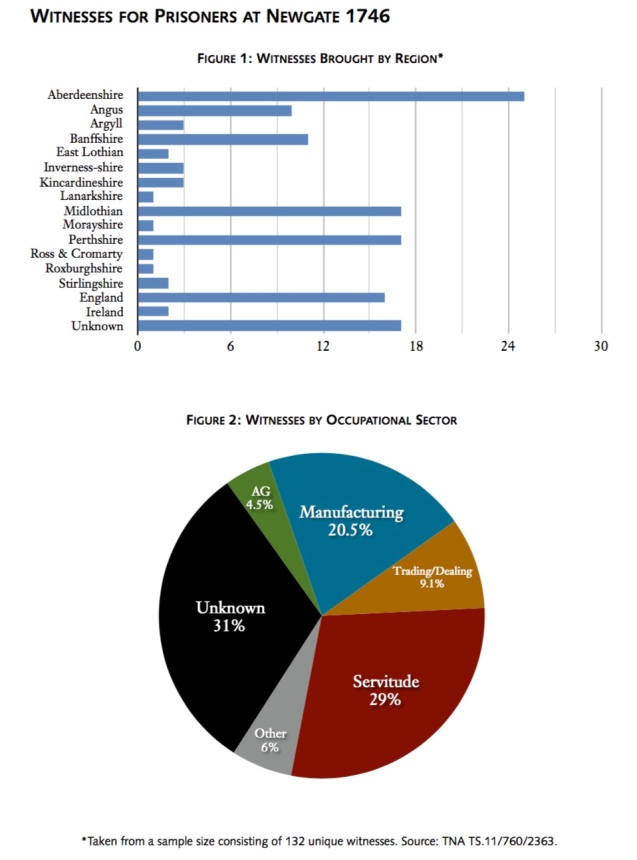

Fletcher suggested there be a minimum of two deponents against each prisoner, with three for those who were ‘most Obnoxious’.[xiii] In practice, however, the ratio of witness to the accused and suspected varied greatly depending on the case. The examination briefs from Newgate prison versus thirty-four detainees feature 132 unique witnesses, broken up into ‘bundles’ with each assigned an identifying number.[xiv] Ninety-nine of them were brought from all parts of Scotland, while sixteen were already residing in England. 112 were also facing trial for their own charges of treason, demonstrating the frequency of alleged Jacobite prisoners turning evidence, presumably to help lessen their own punishments.

At the Southwark trials, eighty-four Jacobite soldiers and twenty civilians participated on the crown’s behalf. In cases there against forty-three of the most prominent rebels, thirteen ‘very material’ witnesses were slated to give evidence against them.[xv] Fifty prisoners lodged in the tolbooth of Aberdeen were witnessed by only ten informers, two of which were also alleged Jacobites.[xvi] In contrast, a list of the early Perth examinations features 132 prisoners spread between at least 150 unique witnesses, most of whom were brought in from the towns and villages within the boundaries of Perthshire. While most of these witnesses testified against only one or two of the accused, a smaller number spoke against upwards of a half-dozen prisoners, with the most active witness each providing evidence in ten different cases.[xvii]

As many witnesses were often themselves suspected or proven Jacobites, they were not always given the most hospitable lodgings during their service to the crown. Kept either in confinement with those on suspicion or in the homes of court-appointed messengers for both supervision and protection, many were essentially treated as if they were prisoners, though almost always being isolated from those against whom they were informing.[xviii]

Witnesses who proved helpful during precognitions and trials were often given benefits by the crown, but their motives for assisting with the conviction of accused Jacobites varied greatly. One of Simon Fraser of Lovat’s witnesses subtly asked for the favour of recommending his brother to a higher post in the British army’s ordnance train in return for his cooperation.[xix] On at least one occasion were potential witnesses promised anonymity by government authorities should they provide helpful information, thereby rendering ‘their intention for the service of the Government more effectual’.[xx] For those themselves under charges of treason, turning King’s evidence could lead to their release on bail or even full pardons. Alexander Stewart and a number of prisoners at Carlisle were brought lists of fellow inmates, and were offered their freedom if they would admit incriminating knowledge of the persons therein. Some rebels were even bribed to provide evidence against extremely valuable prisoners, like Murray of Broughton’s servant MacNaughton, who turned down £30-£40 sterling per annum for as long as he would live.[xxi]

Cumberland’s secretary, Everard Fawkener, admitted to Newcastle that for those who agreed to turn evidence, ‘hope would be a powerful motive on the one side, & fear must operate on the other’, but that ultimately the government would have no control over them once freed after trial. He therefore expressed a macabre desire that those common people who gave evidence and were subsequently pardoned would plead guilty instead of returning home so ‘they may be so disposed of as to be rendered of some use to the world’.[xxii]

Not all witnesses were helpful, of course. John Kent was apprehended and imprisoned in Chester Castle for attempting to persuade one of the King’s witnesses not to offer evidence against the rebels.[xxiii] William Murdoch, a merchant in Callander, was one of many supposedly forced out on no less than three separate occasions by Francis Buchanan of Arnprior. Though at least seven others had spoken against Buchanan, government officials were frustrated by Murdoch’s refusal to do the same, noting that ‘he woud rather Hang than say anything of Arnprior, tho he was the person Inticed him in to the Rebellion’.[xxiv] Patrick Keir had been seen by numerous others carrying arms with the Jacobite army in Carlisle, and offered to testify against over fifty of the ‘principal’ rebels to secure his own freedom. Upon crown solicitor Philip Carteret Webb’s arrival in Carlisle, however, Keir refused to testify and ‘declared all he had said & signd was false’. Webb complained to Newcastle that Keir was ‘a very wicked old Man’, and he was executed at Carlisle in November 1746.[xxv]

Citation Abbreviations:ACA – Aberdeen City and Aberdeenshire ArchivesNLS – National Library of ScotlandPKA – Perth & Kinross ArchivesSPD – State Papers, DomesticSPEB – State Papers, Entry BooksSPS – State Papers, ScotlandTNA – National Archives, KewTS – Treasury Solicitor Papers[i] Memorial for the Keepers (18 February, 1746), NLS MS.17526 f. 134; Pulteney to Newcastle (1 February, 1746), TNA SPEB.44/133 f. 60; James Hulkes to Newcastle (4 August, 1746), TNA SPD.36/86/17.

[ii] Fletcher to Newcastle (15 March, 1746), TNA SPS.54/29/18; Newcastle to Fletcher (21 March, 1746), TNA SPS.54/29/22; Fletcher to Newcastle (14 July, 1746), TNA SPS.54/32/46; Fletcher to Newcastle (7 August, 1746), TNA SPS.54/33/3; Fletcher to Newcastle (14 August, 1746), TNA SPS.54/33/10a.

[iii] PKA B59.30/72 ff. 3-7.

[iv] TNA SPS.54/29/18. According to an inventory of precognitions sent to Carlisle (TNA SPS.54/33/10b), similar bundles once existed from Stirling, Edinburgh, Aberdeen, Kincardine, and at least nineteen other locales. See also ACA Parcels L/H, L/I/4; NLS MS.17515-7.

[v] Francis Wilson to Fletcher, NLS MS.17530 ff. 159-160.

[vi] Fletcher to Newcastle (27 March, 1746), TNA SPS.54/29/28a.

[vii] Newcastle to Fletcher (21 March, 1746), TNA SPS.54/29/22.

[viii] Bruce Gordon Seton and Jean Gordon Arnot, The Prisoners of the ’45 (i) (Edinburgh, 1928), pp. 64-110.

[ix] Alexander Stewart to John Horn (12 August, 1746), NLS MS.17527 f. 60.

[x] Writs of Subpoena (18 June, 1746), NLS MS.17526 ff. 221-222.

[xi] TNA SPD.36/88/60.

[xii] TNA SPS.54/32/35b.

[xiii] Fletcher to Newcastle (10 March, 1746), TNA SPS.54/29/7a.

[xiv] State of the Evidence with Regard to the Rebel Prisoners in Newgate, TNA TS.11/760/2363. These bundles were labeled Chester, Lancaster, or York depending on the witness, which correspond to the castles in which they were confined.

[xv] Prisoners of the ’45 (i), p. 129; TNA TS.20/86/1-5. See also TNA TS.320/86/8 for a larger draft list of initial witnesses.

[xvi] ACA Parcel L/H/2.

[xvii] PKA B59.30/72/9.

[xviii] Prisoners of the ’45 (i), pp. 92-93, 125-126, 175-177; List of Prisoners in Custody of the Messengers, TNA SPD.36/84/9-11; NLS MS.17527 ff. 170-171.

[xix] Fletcher to Newcastle (23 February, 1747), reprinted in Prisoners of the ’45 (i), pp.123-124.

[xx] NLS MS.17527 f. 102.

[xxi] Robert Forbes, ed., The Lyon in Mourning (i) (Edinburgh, 1895), pp. 237-246. MacNaughton refused and was executed at Carlisle on 18 October, 1746.

[xxii] Fawkener to Newcastle (16 July, 1746) TNA SPS.54/32/50. ‘Disposed of’ in this case meant being transported to the New World colonies.

[xxiii] TNA SPD.36/93/129.

[xxiv] Note of Witnesses Against Arnprior, NLS MS.17527 f. 180; Prisoners of the ’45 (iii), pp. 216-217. Murdoch was apparently transported in August 1746 after his trial.

[xxv] Account of Rebel Prisoners (9 October, 1746), TNA SPD.36/88/52; Prisoners of the ’45 (ii), pp. 308-309.

Darren S. Layne received his PhD from the University of St Andrews and is creator and curator of the Jacobite Database of 1745. You can follow his work on academia.edu and he can be found on Twitter as @FunkyPlaid. You’re also welcome to follow the progress of the database project on Twitter at @JDB1745 or via its dedicated Facebook page and website. The content of this post is adapted from a section of Darren’s doctoral thesis, ‘Spines of the Thistle: The Popular Constituency of the Jacobite Rising in 1745-6’.